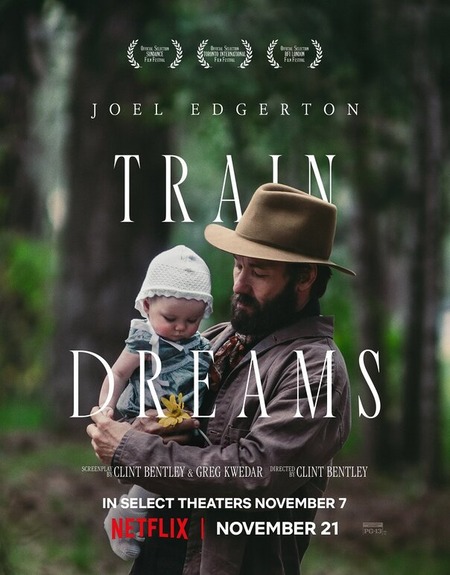

(courtesy IMP Awards)

Grief is rarely a beautiful thing.

What it mourns often is, a time or a person or a place that so captured our hearts that its absence is mourned because the loss of its beauty, of its specialness, is too great to ever be replaced; but grief itself?

No, it is ugly and feral and all-consuming, a thing of grinding sadness and void-heavy nothingness that keeps asking over and over “why, why, WHY?”.

But somehow in the ruminative journey of Train Dreams, directed by Clint Bentley to a screenplay he cowrote with Greg Kwedar, itself based on the book of the same name by Denis Johnson, grief assumes, if not a beauty, then a poetic sheen which allows a brutal and terrible thing to be sat with and appreciated with truth and honesty over 102 cinematically compelling minutes.

Set in Bonners Ferry, Idaho in the early 1900s, Train Dreams explores the heartrending life of Robert Grainier (Joel Edgerton) over 80 years until his death in his small, simple log cabin in November 1968, which was punctuated by losses far too great too bear, none of which made sense to a man abandoned as a child in the town and who craved, more than many people, a sense of belonging, family and community.

It is one of those rare movies that is immersively epic and expansive in scope, taking us across states and through forests and on long train trips – working as an itinerant logger, Robert journeyed far and wide in the pursuit of the livelihood to support his family, the love of his life Gladys (Felicity Jones) and infant daughter whom he worries doesn’t really known because of his necessary but extended absences – but which is achingly emotionally intimate in ways that will make your heart sing and your soul weep in equal measure.

That is an extraordinary achievement, anchored by the director’s ability to keep Robert at the centre of the story even in the most sweeping of northwest USA’s landscapes, filled with great beauty but also incipient threats, chief among them fire, and by Edgerton’s sublimely affecting performance which says so much with the smallest of gestures, the briefest of words and the most subtle of facial gestures.

Edgerton has always been an actor who can say a lot with a little, but in Train Dreams he wondrously and luminously excels, taking us not just into the briefly lovely and mostly grief-stricken world of Robert, which is chiefly lived in interior mode, his words few but his heart big for the right people, chief among them Gladys and his daughter whom he ADORES, but into the heart of what it means to be human.

He shows us both how beautiful the human soul can be but how terrible, the latter not of his making but of some of the men he works with who do some quite terrible things, rooted in bigotry, carelessness and an inhumanity that Robert, a man of great care and thoughtfulness struggles to comprehend or fully understand.

While he meets some truly wonderful people and makes friends with people like ageing coworker Arn Peeples (William H. Macy), a Chinese logger Fu Sheng (Alfred Hsing) and local storekeeper Ignatius Jack (Nathanial Arcand), his is a life marked more than not by witnessing the very dark places people can go to and how destructive their actions can be.

As a man of expansive love and caring soul, Robert struggles to reconcile his inability to stop these terrible things taking place, remarking that it isn’t until very late in his life, when he takes a biplane ride over the countryside around his home, that “as he misplaced all sense of up and down, he felt, at last, connected to it all.”

Dark though some of his experiences are, and marked by grief so all-encompassing you wonder how one man can not just bear them but rise again at all, Train Dreams is, at its core, a stunningly nuanced and quietly beautiful exploration of what it means to truly to truly love, lose everything but to keep going, even if existentially mortally wounded.

What strikes you most strongly about Train Dreams is how unvarnished it all is.

It soars to some astonishing moving highs and documents some truly striking lows but through it all, Bentley doesn’t attempt to portray the expansive good and bad of bring alive with anything but raw, viscerally affecting honesty.

That he and Edgerton do so with an almost whispered, deeply contemplative thoughtfulness is nothing short of miraculous with a storm of pain being contained within the film’s deceptively placid, meditative depths.

There is so much said with so little that you could be mistaken for thinking Train Dreams is far less intense than it is.

But it says and feel a LOT, using its very quietude to catch us off guard, to lull us into a sense that once happiness has been wrenched from loss and pain that it is inviolable, incapable of being lost, maligned or destroyed.

We know better though; even so, it is shocking when the quiet happiness of the first third of the film gives away to significant pain and understandably painful expressions of grief in its final two-thirds and you, along with Robert, must grapple with how life can be so unexpectedly giving and then so daringly and cruelly taking.

Train Dreams does end with a resigned but hopeful acceptance of the way of things at the end, courtesy of the aforementioned plane ride that affords Robert final stage perspective on a life full of heart wrenching twists and turns, so while it possesses more pain that one man should ever have to bear and is a deeply affecting meditation on grief, loss and the inability to accept that which is anything but uncertain, it is, at heart, a stunningly beautiful and cinematographically rich journey into the human soul and the boundless realms of sadness, loss and goodness and hope that lie within.