SPOILERS AHEAD … AND FUNGI MONSTERS FROM YOUR KISSABLE NIGHTMARES …

Apocalypses are never meant to be fun.

The very cadence of the word suggests that, but if you add in the arrival of climate change horrors or monsters or aliens, that point is well and truly driven home as society collapses, terror and privation reigns and people cease being even remotely civil to each other and the dog very much begins to gnaw on its fellow dogs with a vengeance (when zombies aren’t doing that, of course).

You aren’t meant to be happy, to fall in love, to make a life for yourself – life, in apocalypses of any execrable stripe, is all gritty survival and bloody fights for survival and not a nice Beaujolais and rabbit at a finely-carved wooden dining table – and you are certainly aren’t meant to meet the love of your life (again, you aren’t supposed to have a life without enough time, or any time in fact, for any kind of satisfying living).

But in the third episode of the luminously perfect viewing joy that is The Last of Us (adapted from the long-running video game of the same evocative name, love in all its mysteriously wonderful, emotionally transportive and soul-nurturing delight and joy is precisely what we find.

“Long, Long Time” introduces us to Bill (Nick Offerman) and Frank (Murray Bartlett), two men who meet after the Cordyceps outbreak has laid waste to the fragile balancing act of needs and wants that is civilisation and who, quite against all the odds including fungi-driven monsters who run and click with ferocious intent, have forged a life for themselves.

A LIFE. IMAGINE THAT.

More on this deeply moving episode a little later – an episode, by the way, that is quite likely the best episode of any show of 2023 (yes, it’s early on but still …) – because first we have the apocalypse in all its unremittingly bleak horrors with some sassy lines and wide-eyed wonder thrown in, just in case you wonder of little snippets of humanity can find their way into gothic horror shows (turns out they can).

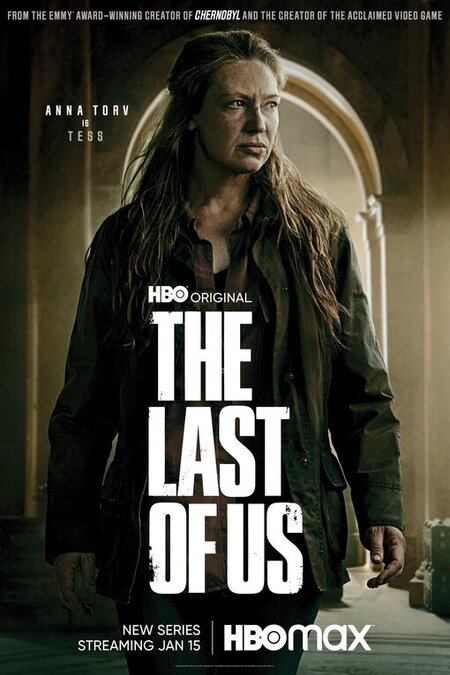

In the second episode, “Infected” and good lord what an apt title with dread woven into the etymological fibre of the word, Joel (Pedro Pascal), his pragmatic lover Tess (Anna Torv) and the person they’re supposed to be ferrying to a Fireflies resistance lab out west (those journeys never end well), Ellie (Bella Ramsey) are making their way, rather gingerly as befits a city overrun with the fungi-laced undead, to the State House of Boston to hand Ellie over to people who will get her where she needs to be.

Those people, alas, are very, very dead, all strewn about the dilapidated building, possibly after one of them got infected, and as we learn later, triggered a kill-everyone-in-the-group response which sensibly but heartrendingly, is how you handle an infection in a group since dead people can’t turn, a decidedly unwelcome turn of events that sees Tess convince Joel, all gloweringly reluctance and simmering trauma, to take her as far as Bill & Frank’s place outside of Boston where they can regroup and figure out how to get their young charge west.

Sounds like a plan, a simply, straightforward plan yes?

Ah, if only there was such a thing at the end of the world; what happens instead is that they encounter a mass of the infected who move as one, fiendishly interconnected by the fibres of Cordyceps that cover and go underneath everything, triggering a flight and fight (both pretty much happen simultaneously) by everyone in the group that leaves Tess explosively dead and Joel and Ellie racing to get the hell out of Boston.

It’s grim on just about every count, and it’s the way The Last of Us deals with this that stamps it as something special, quite apart from its narratively rich talent for constructing stories that rarely put a single, fungi-growth foot wrong, because no matter what happens we see the inherent human tragedy of every single damn moment.

When Tess, bitten, and thus doomed during a skirmish, decides she will blow herself up with the infected to save Joel and Ellie by ensuring they escape unscathed – Ellie gets bitten again but once again, nothing happens to the miracle child of the apocalypse – her final moments, while authentically defiant, are filled with tears, regrets and quite visible longing for everything she will never now not have.

It’s heartbreaking to watch because even though it’s inspiring to watch sacrificial love play out like this, it’s borne out of a tragic loss of choice and the terrible involuntary loss that comes with that, and every last gram of that endless, rolling sadness, which lies just around the corner, for everyone is written on her agonisingly mournful face.

She doesn’t regret what she’s doing but she wishes she didn’t have to do it and The Last of Us takes the time to let her grieve, to be truly human, just as she gives Joel, who is facially mute much of the time with trauma that never leaves him, retreats even deeper into himself, leaving Ellie, who is, for all her sass and wise-arsey quipping, still a teenager who has as many questions as she does moments of grim, survival-enhancing acceptance.

Intensely moving though this episode is it pales to episode 3 which goes deep into what it means to be human in the face of tragedy and loss so monumental that dealing with it should be all but impossible on anything but the most grimly utilitarian of levels.

In this touching tribute to love’s ability to survive in the face of just about anything – and by love, we mean that down-in-the-trenches, muscular love that takes handles anything that comes its way; a far cry from the blithe frippery of banal greeting card sentiment which wouldn’t make it out the bunker door in an apocalypse – that gives this moving timeline of a relationship so much damn emotional weight.

When the end of the world happens, Bill is almost cock-a-hoop with joy, all his survivalist prepping which is EXTENSIVE (two walls of guns anyone?) proving itself to be time well spent.

He is near joyous at the departure of his fellow towns folk who leave him an easily defensible small patch of urbanised land – by easily defended we mean an extensive system of barbed wire, booby traps and explosive everythings – and hunkers down for a life of fine food, wine and the isolation that comes from the rest of humanity being sent away to Quarantine Zones aka QZs(or if there’s no room for them, NOT; the skeletons along the road indicates what happened to those unlucky enough not to find sanctuary).

Thus, he is none too pleased when Frank, fleeing the collapse of the Baltimore QZ, stumbles into one of his traps, an accidental infiltration that goes from grudging hospitality to full blown love over twenty years, from when the apocalypse starts in September 2003 (we get an explanation for why and how it happens – the carbs-based cause is touched on at the start of episode 2 – and it’s brilliant! See The Walking Dead, you don’t have to be all myseriously mysterious, answers actually do work especially when it’s accompanied by some D&M-ing by Joel and Ellie, who’s enraptured by the idea of plans and cars equally) right through to August 2023 when Frank’s terminal condition necessitates a course of action that is heartbreakingly final.

Their love is portrayed with care, sensitivity and thoughtfulness, and while it will no doubt trigger every conservative under the sun who will rail that no LGBTQ romance could possibly be that pure, the truth is it absolutely nails how tender and mutually supportive such a union can be.

Taciturn Bill, who is against he and Frank becoming smuggling comrades-in-arms and then friends with Joel and Tess, and vibrantly outgoing Frank who wants to keep the town shipshape and nice for them and their friends and to grow strawberries as a delicious surprise for his great love, are LOVE so beautifully realised and expressively lived that you are drawn into their story in ways that are complete and unending.

They prove that love can survive just about everything, and while those scenes where they take some rather final steps will BREAK YOUR HEART with the depth and care of their love (“I’m old. And I’m satisfied. And you were my purpose”) it establishes The Last of Us as something truly special and utterly remarkable.

After an opening two episodes which expose the nightmarish hell of a world turned to fungi, we are shown that humanity can survive the end of the world and that it is rich and beautiful and wonderful, and while it’s not an antidote to the dangers awaiting Joel and Ellie on their journey, it does prove that The Last of Us understands that life can survive ever-present death and that it might even occasionally get the upper hand (even as we weep at the sheer beauty and loveliness of it all in tow performances that should earn Offerman and Bartlett Emmys).

Where that leaves our intrepid twosome, who are quickly developing into an entertaining if emotionally affecting double act, is something for future episodes to explore, but suffice to say, the grimness and joy of these two quite different episodes proves that this video game adaptation is really something quite special.