At first glance, Babes in Toyland, Disney’s 1961 aspirational attempt to create a movie as magically transportive and musically-rich as The Wizard of Oz – they didn’t but that was a pretty tall order anyway – doesn’t come across as a Christmas film of any stripe. (The festive angle doesn’t make an appearance until the final third of the film but more on that later.)

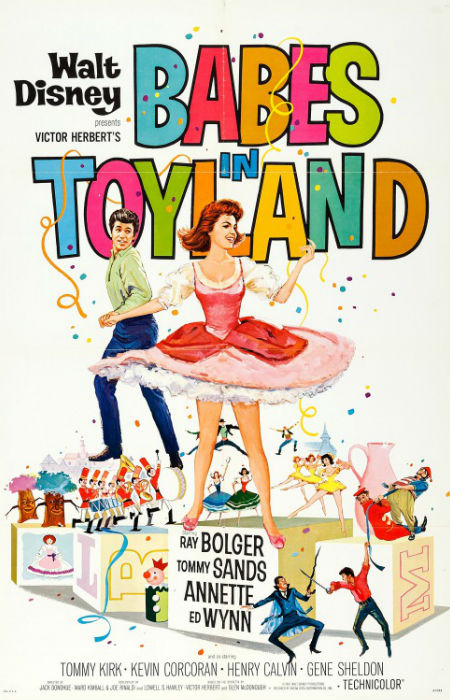

Based on Victor Herbert’s 1903 operetta, which Disney, as is their wont, played around and changed to a fairly-considerable degree, Babes in Toyland is ostensibly a Mother Goose (Mary McCarty) tale about the impending marriage of Tom Piper (Tommy Sands) and Mary Mary Quite Contrary (Annette Funicello), who actually has silverbells, cockleshells and little maids all in a row (who looks like psychotropic leftovers from a budget horror movie) as the rhyme dictates.

(Also making an appearance, this being a nursery rhyme land of sorts with people living in giant shoes and pumpkins, are Jack and Jill, looking quite uninjured from their tumble down the hill, Little Bo Peep, who is a melodramatic alarmist who puts almost no effort into finding her sheep, and Jack be nimble whose sole talent seems to be leaping over giant candlesticks.)

Beginning as stage play introduced by Mother Goose and her goose Sylvester, who has a way with oneliners, snappy comebacks and cynical distrust of the obviously evil antagonist Barnaby (Ray Bolger, who ironically enough did star in The Wizard of Oz, a far superior film), the film soon assumes a reality all of its own, although the backgrounds retain a theatrical look and feel to them throughout.

Clearly we are meant to be transported from the get-go into a land so magical and wonderful that all we’ll care about is the happiness of Tom and Mary, the trouncing of the pantomimely-wicked Barnaby and the restoration of the contented bonhomie that seems to be the natural default setting of musicals everywhere.

But intention and execution, as we know all too well, are too completely different things and though Babes in Toyland aims for the kind of deliriously-upbeat joy and our-heroes-are-in-danger- what-will-become-of-them tension of most musical extravaganzas, it never really quite makes it.

In fact, especially towards the end, you begin to wonder exactly what writers Lowell S. Hawley, Ward Kimball and Joe Rinaldi and director Jack Donohue were smoking as they made the film.

It is as trippy and weird as its comedically sweet, a visual treat for the eyes with its insistence on technicolour brilliance in almost every scene, but for all that vivacity and songs that attempt to leap off the screen with overplayed exuberance, Babes on Toyland never really finds any sort of meaningful momentum.

The songs, though seemingly made to order for such a brightly-effervescent undertaking, never really fly; the cast give it their call, of course, with some fine performances, most notably from the two goons, moronic Gonzorgo (Henry Calvin) and comically-silent Roderigo (Gene Sheldon) who are hired to help Barnaby steal Mary as his bride, and Annette Funicello and Tommy Sands are virtuously, and unrelentingly, lovely but they can’t compete with songs that sound like they were written from the musicals playbook with no attempt to create lastingly unique classics.

In their own scenes, the songs come alive to an extent, and you’d be a complete Grinch not to be swept up in them in some fashion, but you aren’t humming them later, and there’s a reason why the songs haven’t entered the popular musical lexicon.

In other words, sweet and jaunty enough to serve the threadbare, later off-the-rails weird plot, but really nothing more with the lyrics caught in a simple rhyming spiral that never gets away from Song Words 101.

The characters too are tropes that never really come alive with their own vibrant personalities or strong sense of selves.

The Sole exception to this is Barnaby and his two greedy henchmen who go for broke in the hamming-it-up stakes, with Gonzorgo and Roderigo channelling their inner Laurel and Hardy who, fun fact incoming, made a version of this story back in 1934 (which I suspect, given the calibre of the two performers, are writers and comedians, would have been immeasurably better than Disney’s).

The songs and characters are but two examples of a general approach which seems to have been inspired by a desire to create a lasting holiday classic by ticking all the usual boxes and nothing more.

It is enjoyable in its own way, and certainly once Tom and Mary, and their orphan brood of Children of the Corn extras make it through the Forest of No Return (again The Wizard of Oz and The Princess Bride came up with far superior magical forests) and into the garish fabulousness of Toyland where the demented Toymaker (Ed Wynn) and his assistant Grumio (Tommy Kirk) are trying to get all the toys made for Christmas (Santa is nowhere to be seen; clearly he is a customer and nothing more), things do pick up a little.

This part of the story has its own manic madness at play, as Barnaby and his goons seek to realise their plans with all kinds of tomfoolery and misuse of shrinking guns and warring toys.

None of it really makes sense – at one point Mary is in a perfect position to save the day but doesn’t, leaving Tommy, the man, to best the baddy and get everything shipshape again – but it’s so over-the-top, colourfully-ridiculously, and Ed Wynn’s performance especially is such a comedic joy, that you go along with the final third of the film which ends, rather abruptly, with what feels like a tacked-on happy ending.

By no means is Babes in Toyland a trainwreck, with the film doing its best to go through the singing-and-dancing motions, and even be a little seditious at times (Roderigo is murder happy and tries at one point to actually give the finger), but while it’s charming, fun and colourful, it always feels like a photocopy of bigger, brighter and better musicals that never really finds its feet, conjuring up not so much magic as a rather less prosaic version of real life.