There’s an idea prevalent in society that grief unexpressed isn’t grief at all.

In other words, if you’re not wailing and crying and gnashing your teeth like an Old Testament prophet clad in sackcloth and ashes, then are you really grieving?

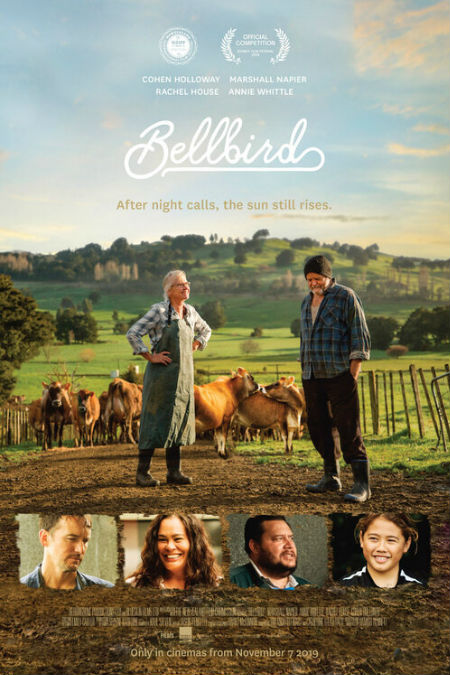

It’s an idea that is gently and thoughtfully challenged by New Zealand writer-director Hamish Bennett’s debut feature, Bellbird, which had its world premiere at the Sydney Film Festival last night.

In this most charming, heartfelt and emotionally naked of films, which says an immense amount by having its main characters say not much at all, we get a glimpse into the way grief looks when it happens to someone to whom a bold and forthright expression of emotions is anathema.

Dairy farmer Ross (Marshall Napier) is a man of few words, a taciturn bloke’s bloke who is happy in the silences, and who sees no need to fill them unless it’s absolutely necessary.

By way of absolute contrast, his wife Beth (Annie Whittle) is as garrulous as they come, an extrovert with a legion of friends, a steady line of chatter and close involvement in the local choir.

She is everything Ross is not, and yet, even though she calls her husband a “grumpy old shit” at one point, there is a great deal of love and affection between the two, evidenced in one small but charming scene when Beth walks into the kitchen while practising with her choir outside, remarks that if Ross wants more of this – she playfully whacks her bum – he’ll have to come outside.

Ross, of course, would sooner walk through lava that join the hubbub of a choir gathering, but as Beth walks out, he smiles as his wife watches, a current of love and belonging racing between the two with almost no words said.

It speaks to the whole narrative approach of this gorgeously-immersive, heartfelt film which exists in the quiet spaces inbeween, in the birdsong, the cows lowing, the rustle of the trees as the wind softly wanders through them.

In Bennett’s perfectly-judged world, there is no need for extravagant sound or gesturing because the finely-etched characters are able to communicate so much in the silences.

And there is a great deal of that silence with neither Ross or his son Bruce (Cohen Holloway) big on talking; so when Beth is tragically killed, presumably in a car accident, there is no wailing, no collapsing in on themselves, no Oprah-like discussions of feelings.

Instead, Ross throws himself into his work on the farm, dragging Bruce, who has returned to help him, along in his non-communicative wake.

The only conversation breaking the quiet spaces after Beth’s sudden, world-shattering departure, is cheeky school boy Marley (newcomer Kahukura Retimana) who, with a natural ease neither father or son possesses, helps out on the farm, chattering as he goes.

He’s not only good at his job, he’s also wholly at home on the farm in a way Bruce is not, with Ross’s supposed heir far more at ease with repairing the broken treasures that flow into the rubbish tip/recycling centre where he works with owner Connie (Rachel House) than reaching into cow’s rectums to help with problematic births.

It might seem at first that neither man is capable of feeling or are in unspoken denial of their feelings, but Bennett beautifully demonstrates that lack of expression does not equate to some sort of monstrous emotional nothingness.

In scenes alternately funny and poignant, and sometimes both, we come to see in ways big and small, usually the latter, how both men not only care for each other but are acutely aware of the gaping void that has opened in their family.

They may not express it, but the great hulking presence of grief looms at every turn, infusing the simplest or most routine of tasks with profound meaning and emotion.

Take the moment when Connie’s aggressively abusive ex comes to her workplace, demanding that she get in the car for a conversation; Connie refuses but her ex refuses to take no for an answer until Bruce, a man not known for demonstrative accounts, backs her up, both verbally and physically.

Having barely seen off Connie’s ex, and covered in blood from the altercation, Bruce breaks down, sobbing as he watches the car drive off.

Similarly, Ross breaks down at another key moment, both scenes underscoring with a heart-tugging simplicity how deep the rivers of grief run and how much Beth’s absence is affecting them.

Bellbird, which takes its name from Beth’s favourite song, a piece of music that plays a pivotal role in the growing willingness of Ross and Bruce, supported by friends like Connie and vet Clem (Stephen Tamarapa), to begin talking about the great unspoken shared grief between them, is a sweetly-affecting gem.

Never once ramping up the intensity of its narrative nor its predisposition of its two main characters to stay quiet rather than let it all hang out – in marked contrast to Connie, Marley and Clem, all of whom are happy to wear their hearts on their sleeves, and who, by their openness provide much of the dry comedy that percolates through the film – Bellbird is a quiet tale that speaks volumes by simply letting its emotionally-rich, thoughtful story unspool at its own life-driven space.

This is a narrative lived in the sparse moments between epic events, where the day-to-day is not punctuated by great epiphanies or theatrical declarations but by a muted understanding that life, even its most traumatic moments, happens in small, vulnerable degrees, many of them unremarkable save for the fact that they are often ripe with emotion and insight which isn’t always articulated (nor does it ever have to be).

This beautifully-executed film, charming and funny, heart-full and intense in a nuanced, understated way, celebrates those quiet moments and the softly-spoken people who inhabit them, acknowledging that there is always a reckoning of some kind but not always at top volume or in an overly-dramatic fashion, and that that is okay, entirely valid and just as meaningful and profoundly healing as shouting it from the mountaintops.