Nebraska is a remarkable movie.

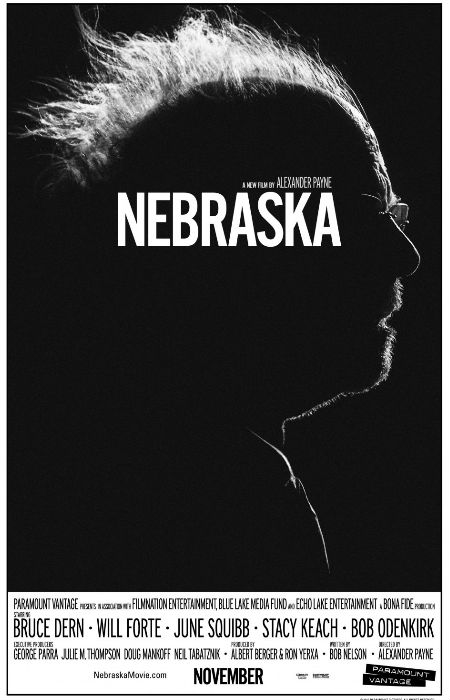

Not least because director Alexander Payne (About Schmidt, Sideways) chose to film his exploration of a father (Woody Grant played by veteran actor Bruce Dern in fine form) and a son (David Grant, rendered with exasperated poignancy by Will Forte) finding a meeting point of sorts on a road trip, in luminous black and white.

Cinematographer Phedon Papamichael, who has worked with Payne on Sideways among other projects, fills the monochrome with all manner of shades you don’t expect to see, the vast could-filled landscapes of Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska coming alive with a pastel of a thousand and one rich slivers of grey.

And while it was supposedly filmed this way against the wishes of releasing studio Paramount, it is hard to imagine it existing any other way.

Quite apart from anything else, the choice of black and white reinforces the sense that both father and son have found life to be a less than thrilling kaleidoscope of vibrantly realised possibilities.

A Korean War veteran who never quite made the transition back to civilian life, and used the bottle to cover up his inability to bridge the gap, deleteriously affecting his wife and two sons along the way, Woody is a trusting man with a kind heart who, according to his son and greatest advocate, David, simply believes what people tell him.

Now in his later years, and afflicted by early onset dementia, or possibly simply a disengagement with life which disappointed him many years earlier, he accepts without question the veracity of a letter he receives from a magazine promotions company in Lincoln, Nebraska, proclaiming him their latest millionaire.

Ignoring the small print, which couches his win as conditional upon being the possessor of the winning numbers, and neglecting the fact that this sort of promotion is a scam, he sets off repeatedly to walk to Lincoln to collect his money.

Refusing to heed almost apoplectic entreaties from his hilariously honest wife Kate (June Squibb), who despite obviously caring for him wants him in a home, and his other “successful” newsreader son Ross (Bob Odenkirk) to cease and desist his quixotic journeys, he believes, as only a person bereft of any other possibilities could be, that this is the real deal and the satisfying conclusion to his life.

It isn’t the money that enthrals so much as the ability it will give him to buy a new truck – he no longer has a license making this particular purchase well near useless but symbolically important nonetheless – and an air compressor, to replace the one stolen 40 years earlier, so he says, by old business associate Ed Pegram (played with delicious callousness by Stacy Keach).

And so David, a man recently split from his girlfriend Noel (Missy Doty) who dumped him because she correctly perceived him to be “stuck” in his life (“Let’s get married, let’s split up. Let’s do both. At least it would be something.”) decides to take his dad to Nebraska, hoping for some kind of redemptive time together (and discovering along the way that his father is a real person who lived a hitherto unrevealed, to his son at least, life).

That he gets it is not necessarily a foregone conclusion, but get it he does, despite his father’s implacable estrangement from anything approaching meaningful contact with others, and it’s the way it unfurls against grubby money-snatching tactics by Woody’s extended family that give Nebraska such a refreshingly unblemished tender heart.

So light and well-orchestrated is Payne’s touch, that the moments of true emotional connection never feel manipulated or overplayed, whether it’s Kate’s tender kiss on Woody’s forehead after a litany of complaints and pejoratives against her husband of many years, or David’s repeated unfailing willingness to stand by his dad even when it becomes difficult to do so.

It is a portrait of love lived in the realness of life, neither candy coated nor gritty, existing somewhere in that zone that Hallmark never ventures – the ebbs and flows, and the ins and out of the everyday, a place where affection, care and love often get lost in the rush to get ahead, and the resulting recriminations when that fails to happen as envisaged.

The road trip aspect of Nebraska is vitally important giving the relationship between Woody and David, and their connections to the rest of their immediate family – their extended family is, despite all the platitudes, nursing grievances without number at Woody’s supposedly poor past behaviour, an accusation Kate rejects with fiery power in one quite remarkable scene – a chance to breathe away the slough of their moribund lives in Billings, Montana.

Nebraska is that rarest of beasts, a movie that balances life as it really is, with all its failures, half-truths and frustrations with the innate sense that love survives somehow through it all if you’re able to persist in looking for it.

It may sound insufferably twee to describe it that way but Nebraska never delves into cheap and easy accessed answers or emotions, it’s happy ending of sorts rooted quite firmly in the bleakness and monochromatic nature of life, where every victory or sweet moment is hard fought for, and all the more worthwhile for that.