There is something inspiring about watching people realise their dreams.

It’s not simply being party to the material fulfilment of something that has often just existed in the intangible reaches of the heart and the mind; it’s the look on a person’s face when the hoped-for being the lived-out and all the sacrifices and time and energy expended finds physical, touchable form.

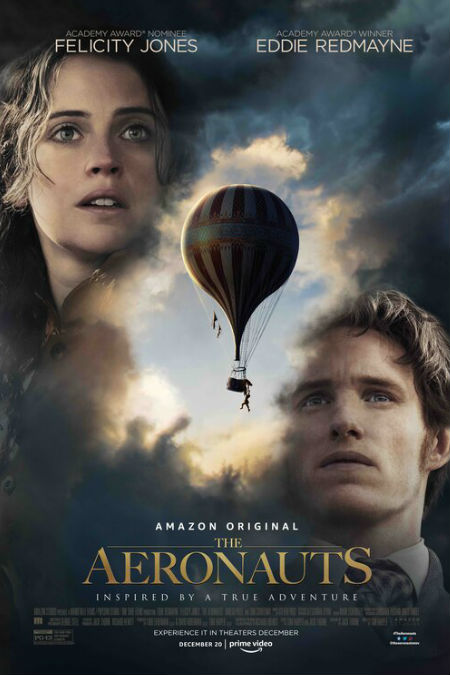

But as the Tom Harper-directed The Aeronauts makes thrillingly clear, the culmination of all the hoping and longing is not without its risks, especially when you are James Glaisher (Eddie Redmayne), a scientist and nascent meteorologist who is desperately anxious to prove to his fellow cruelly-sceptical men of learning that it is possible to predict the weather.

To do that, of course, he has to ascend high into the atmosphere, something only possible for a man of limited means by allying himself with celebrated aeronaut – the term used for those flying hot air balloon high into the heavens – Amelia Wren (Felicity Jones) who, like her inexperienced co-pilot, in dealing with a number of earthbound issues of her own.

Not least is the fact that her husband and love of her life Pierre (Vincent Perez) died two years earlier in a ballooning accident at high altitude (how exactly and why is explained in a moving flashback), making her return to aeronauting highly emotional and problematical and a source of consternation to her sister Antonia (Phoebe Fox) to whom she is quite close.

The meeting between Glaisher and Wren is told in flashback, with the majority of the film concerned with the pair’s ascent into the highest levels of the atmosphere, an undertaking that proving the making of Glaisher’s reputation while further cementing Amelia’s already stellar one but not without a number of close calls that make fulfilling dreams look like a very dangerous business indeed.

For all of the emotional resonance the film possesses, what is really on offer here is a rip-roaring “boy’s own” adventure that requires a happy suspension of disbelief to make it work.

And work is most sensationally does.

From the flamboyantly theatrical scene which launches the balloon aloft to the cheers from an appreciative crowd of 10,000 or so people in 1862 London – the aim is to go higher than the current record of 23,000 feet held by the French – where the differing approaches of gung-ho Wren and soberly scientific Glaisher come into sharp focus, to the ever-escalating tension inherent in their bold undertaking, The Aeronauts pushes the envelope both narratively and in terms of the sheer cinematic bombast on screen.

This is a film that knows it is telling a fantastical version of history – two aeronauts, James Glaisher and Henry Coxwell, did ascend to just 39,000 ft in 1862 via a coal-powered gas balloon, setting a new world flight record – and runs with its hyperbole, or rather rushes skyward, telling a very human story of dreams and aspiration, loss, grief and rebirth against a story so boldly imaginative that you wonder if the action isn’t going to overwhelm the quieter moments.

And yet, for all the edge-of-the-seat moments and they are many and tension-filled, and brilliantly, gorgeously over-the-top, The Aeronauts also boasts scenes of such rare and quite beauty that they almost take your breath away (metaphorically for us, literally, at one point, for Wren and Glaisher).

Take the moment when, after a rough ride through a layer of titanically violent storm activity, they reach a plateau of sorts above the clouds where the sun breaks through, the sky is blue and the silence stands in stark contrast to the noisy hustle-and-bustle of mid-nineteenth century modernising London.

After the fearsome battle simply to stay aloft, and thus, importantly, alive, the time Glaisher and Wren spend marvelling at the beauty is therapeutic for them (and us), a reminder to them both, but most particularly to Glaisher who is obsessed with fulfilling his dream to the extent that he often neglect to take stock and enjoy the journey, that there is great value, even in the midst of making history to stop and smell the figurative roses.

It is these calmer interludes, which Harper allows to breathe and come alive with their own thoughtful energy and verve that balance out the more extreme parts of the film where reality, much like the then-current understanding of the emerging field of weather science, is pushed to the limit.

To be fair, there are more than a few times in The Aeronauts where the coincidences and narrative contrivances are so nakedly obvious that it would all too easy to dismiss them as empty blockbustering.

But thanks to the finely-written characters of Wren and Glaisher, who benefit greatly from judiciously used flashbacks which add to rather than detract from the action at hand, and sublimely good chemistry between Redmayne and Jones, the more extravagantly unreal moments feel far more grounded than they should and create a rich sense of humanity among the aerial maneuvers.

Given the scope and enthralling bombast of the story which, even without cinema’s narrative augmentation, would be mightily impressive, this is quite an achievement and speaks to the fact that like many epic accomplishments, this one is very much rooted in the hopes and dreams of two very flawed but hopeful people.

Take away the human angle, and that must have been tempting at times, leaving the action to dominate, and you have ended up with a story that would looked and felt larger than life abut empty and devoid of any real, affecting emotion.

The pleasing genius of The Aeronauts is that it manages to have its epic action and more intimate, deeply human moments too, proof that you can tell a brilliantly engaging adrenaline-pumping story without sacrificing the very humanity that gave it birth in the first place.